About me

I’m Joe, I’ve just finished my PhD at the Institute for Particle Physics Phenomenology (IPPP) in the Department of Physics at Durham. I’m part of the Centre for Doctoral Training in Data-Intensive Science and my research has focussed on using machine learning and other emerging technologies in particle physics, as well as in the humanitarian space.

In 2018-2019 I was a Research Fellow with the United Nations (UN) in New York. Since 2019 I have also held the position of Industry Research Associate at the RiskEcon Lab, part of the Courant Institute of Mathematical Sciences at New York University. I particularly enjoy collaborating with researchers across different fields and am beginning a full time research position at the UN in September.

Colliding particles

Particle physics is a naturally interdisciplinary field. In Durham we work a lot on how we can use computational methods to simulate what happens when particles collide at experiments such as the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) at CERN. To build these models use techniques from multiple fields and work closely with computer scientists and mathematicians. The LHC speeds up particles (specifically protons) to nearly the speed of light and then smashes them into each other and measures what happens. The idea behind this is to try to understand more about the fundamental particles (like the famous Higgs Boson) which make up our universe, and to see if there are any deviations from current theories. In order to understand what should happen and what could happen according to different theories, we use large computer models which mimic reality and which allow us to probe multiple possible scenarios which could occur. However, these simulations are very challenging and can take a long time to run.

Over the course of my PhD in particle physics Durham, I have focussed on ways to use new technology, specifically machine learning methods, to speed up various parts of these time consuming simulations. Through using a mixture of computer science techniques, and particle physics knowledge, we found that a computer has the potential to learn what some of these particle interactions look like, meaning we can partly bypass the time consuming calculations that previously had to be done. This research also introduced me to many of the techniques underlying these large simulations, such as the statistical methods for simulating many different things that can occur in particle collisions.

Human interactions

The machine learning techniques I was using and developing in my research could also be applied to problems faced during the humanitarian crisis response work of the UN. During my PhD, in 2018 I had the opportunity to work at the United Nations on a Research Fellowship at UN Global Pulse (UNGP), and continued to work with them afterwards. As an example, I worked closely with the UN’s Satellite Centre (UNOSAT) who use satellite imagery to pinpoint where and when flooding occurs. To speed up the process, we designed a machine learning method which taught the computer how to spot where floods are in a satellite image itself and has since been used to produce the first ever flood response maps issued by the UN which were created by a computer.

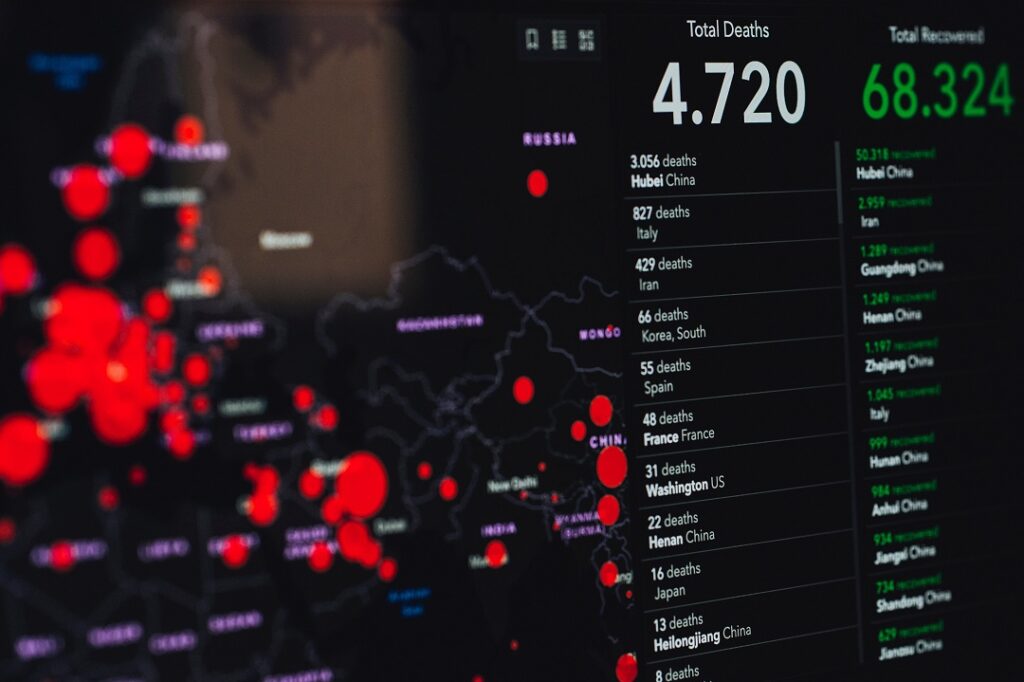

During the COVID-19 pandemic, I have collaborated with researchers at Durham and University College London to build a computer simulation to understand how the virus might spread in a given population by modelling what people do in a day, where they go, who they interact with, and how likely an infected individual might be to pass on COVID-19 to someone else they meet. Our model simulated the movement of people at the individual level – a bit like a video game. We began by modelling the population of England, which meant we had to keep track of around 55 million people in the model, and running it multiple times to explore what might happen under different scenarios. To do this, we used many of the techniques underlying the particle simulations I had worked with, however, instead of simulating millions of particle interactions, we were simulating millions of human interactions.

In parallel, we also worked with other universities and with agencies across the UN, to adapt the model to the case of a refugee settlement. Specifically, we focused on the Cox’s Bazar settlement in Bangladesh, the largest such settlement in the world where there is a high risk of disease spread. Here, we worked with decision makers based in the settlement to simulate how the virus would spread if different mitigation measures were put in place – such as mask wearing, or changing the rules on quarantining people with symptoms – to make better use of the settlement’s limited resources.

Interdisciplinary collaboration

The techniques I have been exposed to during my particle physics PhD have many applications to other fields, and I have enjoyed working with humanitarian experts to see how they can be applied to help decision makers and responders in crisis scenarios. Indeed, in order to solve the world’s toughest problems, and overcome the present and future challenges we face, we will need more interdisciplinary collaboration so we can better leverage our shared knowledge.

Now that I have completed my PhD, I look forward to joining UNGP full time as a Postdoctoral Researcher and continuing to collaborate with teams in Durham and elsewhere.

Discover more

About postgraduate study at Durham here

About studying Physics at Durham here

Download our latest postgraduate prospectus and college guide here.