Unlike my fellow Ph.D. students, I spent a quarter of my summer deviating from my thesis and diving deep into the research project ‘Legacies of Enslavement and Colonialism at Durham University.’ My job entailed assisting Dr Jonathan Bush, University Archivist in the Archives and Special Collection at Palace Green Library, with archival research to trace connections between slavery and our university.

Being the Watson to Sherlock/Dr Bush, I sifted through institutional records of the University for connections between donors, students, and staff of Durham in the 19th century and their links to the slave trade and slave plantations.

History of Durham University and Enslavement

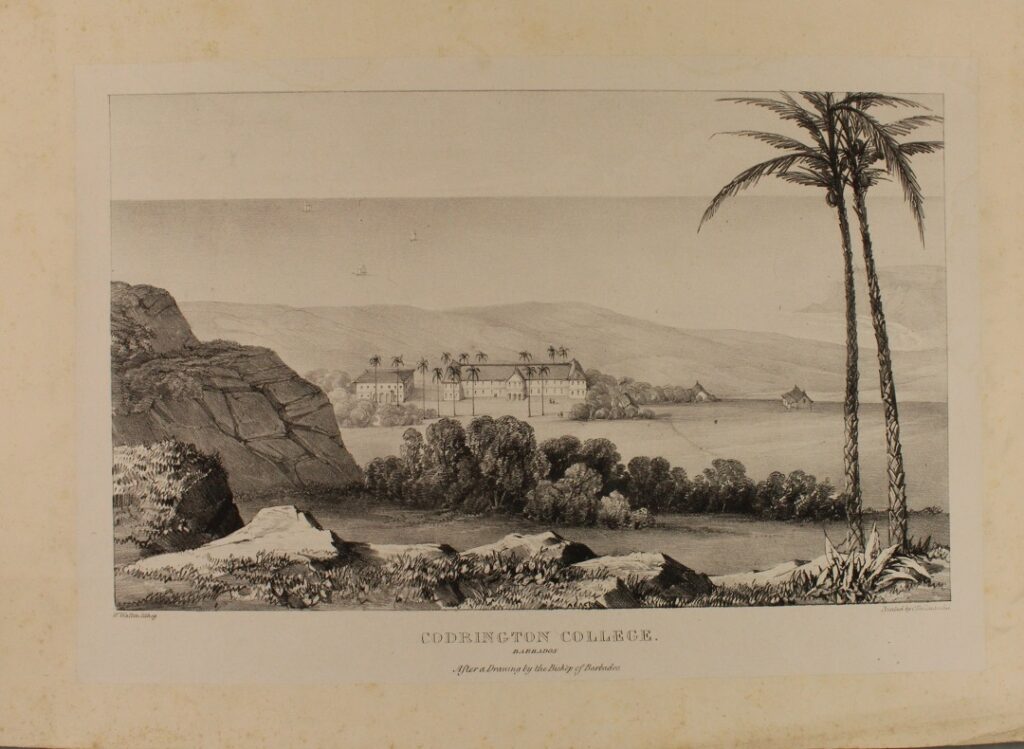

Durham University was established in 1832, a year before the Slavery Abolition Act in the UK was passed. Nearly fifty years later Codrington College in Barbados (1875-1965) and Fourah Bay College in Sierra Leone (1876-1967) were affiliated with the University, with subjects like theology and education being taught there and administered by Durham University.

Institutional records about these colleges proved to be fertile ground for the study of colonialism and indicated links to slavery. For instance, previous scholarly research has connected the SPG (Society for the Propagation of Gospel in Foreign Parts), slave plantation, and Codrington College.

However, we aimed to find concrete links between members of Durham University and slavery. We hoped to isolate the names of potential slave benefactors and cross-check their names with the UCL’s (University College London) Legacies of British slavery database.

I endeavoured to sift through the three volumes of Treasurer Bills from the 1830s to 1870s of Durham University as well as Property Records of the University from the 19th century. Along with these records, I explored the meticulously digitised copies of Durham University Calendars that consist of names of students and staff members of Durham University, Codrington College, and Fourah Bay College.

Stumbling through UCL Slavery Database

Through these records I cross-checked the names of individuals who donated to the University, members of staff as well, and students who spent the majority of their time studying in Durham and later became prominent members of society. Although many names were present in the UCL database, I faced a roadblock.

While few entries in the UCL portal have biographical information, many entries do not provide enough information about slave benefactors to ascertain identities. It is nearly impossible to nail the identity of individuals unless it is verified through other databases, such as the genealogical database stored in the National Archives.

Therefore, I had to walk away with the knowledge that while there would have been a handful of individuals associated with the University who had links to slavery, more hours of research need to be devoted to studying the connections between enslavement and Durham University.

The joy of working in Palace Green Library

My time in the Palace Green Library was amply rewarded, as I became acquainted with its rich and unusual collections such as the Sudan Archives. The archivists, conservationists, and librarians are wonderful hosts who helped me every step of the way and made my work environment a welcome refuge amidst the turmoil of doctoral study.

I believe this project is a rich, untapped wealth of information that can shed light on the multifaceted intercontinental history of enslavement and colonialism in the UK. Considering the presence of numerous well-preserved archives at Palace Green, I am hopeful we will soon learn more about links between slavery, anti-slavery, and Durham University through the

progression of ‘Legacies of Enslavement and Colonialism at Durham University.’

Discover more

Learn more about Legacies of Enslavement and Colonialism at DU project.

Take a closer look at Palace Green Library